Day surgery is a process; not a procedure. It is a planned elective pathway which commences with first patient contact and finishes at final discharge. In many countries the term ’Ambulatory Surgery’ is more commonly used but the two terms are synonymous. The IAAS definition of day surgery is:

An operation/procedure (excluding an office or outpatient operation/procedure) where the patient is discharged on the same working day.

Though there remains variability worldwide with some countries accepting a 23 hour stay as day surgery the IAAS defines this as Extended Recovery or Short Stay Surgery as it fails to ensure the full gain for the hospital and the patient.

Day Surgery is not a new concept. James Nicoll, widely regarded as the ‘Father of Day Surgery’ reported his experience of performing nearly 9000 paediatric day surgery cases at the Sick Children’s Hospital and Dispensary, Glasgow, in the British Medical Journal in 1909 (1). His cases included elective procedures for hernias, hare lip and cleft palate, and talipes but also emergency day surgery procedures for congenital pyloric stenoses and depressed birth fracture of skull. Modern day surgery has its origins in the 1980’s primarily stimulated by the reduction in costs of day surgery compared to inpatient surgery. The philosophy of day surgery is to minimise the patient’s time in hospital by removing the need for inpatient stay the night before and the night after their surgical procedure. This requires dedicated protocols and guidelines and careful management of the patient’s expectations.

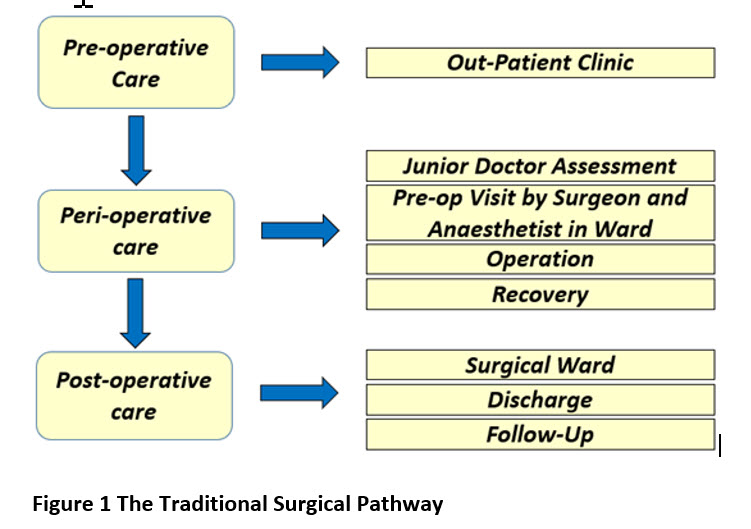

Before the development of day surgery pathways, the process of preparing the patient for surgery was lengthy and time-consuming (Figure 1). The surgical pathway can be subdivided into three main domains of pre-, peri- and post-operative care. At the surgical out-patient clinic, the patient was commonly seen by a junior doctor who made the decision to treat and added the patient to the waiting list. On admission to hospital the day before surgery, the patient was clinically assessed for fitness for surgery. Later in the day, the patient was seen by a senior surgeon and anaesthetist. Unfortunately, late cancellation due to fitness issues was not uncommon. The following day, the patient was taken to the operating room and their procedure performed. After recovery, the patient was returned to the surgical ward and remained in hospital for at least one night, but commonly longer, even for minor or intermediate procedures.

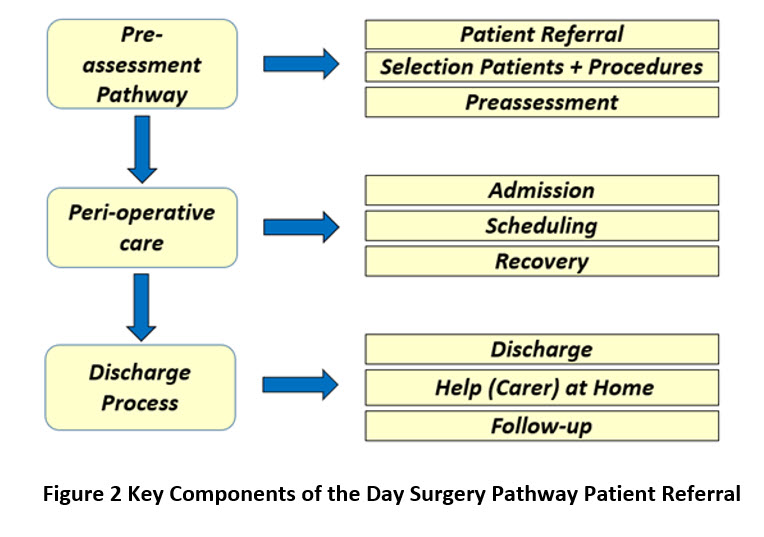

The introduction of day surgery principles to the traditional pathway, streamlined the patient experience. The first review of the patient occurs in primary care. This should take place with knowledge of the procedures that can be carried out on an ambulatory basis. At specialist referral, if the patient is suitable for day surgery management, there is an expectation that the patient will follow a quality assured process of a defined and streamlined pathway (Figure 2).

In countries with a developed Primary Care Service – Primary Care Practitioners can have an important role when referring the patient to Hospital Specialists. The referral letter should succinctly include the presenting complaint, the past medical history including co-morbidities, medication and allergies, blood pressure, body mass index (BMI) and relevant diagnostics. Before referral, a series of key questions should be considered.

Is the patient fit to proceed to surgery?

Long term conditions such as hypertension, atrial fibrillation, diabetes, and anaemia may require optimisation before referral, otherwise a surgical delay will occur while the patient is referred back to primary care for review and treatment.

Adverse lifestyle choices which may impact on the success or safety of an operative procedure such as smoking, body mass index, alcohol consumption and recreational drug use, require lifestyle advice.

Does the patient understand that the referral may lead to surgery?

If this hasn’t been discussed, an uninformed patient may refuse a surgical solution, leading to a waste of resources.

Does the patient understand the potential timescale?

Surgery will be offered according to the urgency of the condition and the current waiting times at the hospital.

Is the potential operation suitable for day case surgery?

It is helpful if the referring Primary Care Practitioner has knowledge of procedures that are suitable for day surgery as they can inform the patient at the beginning of the pathway that they might be able to have the procedure as a day case. This knowledge comes with experience but can be helped by provided those referring patients with a list of procedures that are potential day case procedures.

The function of clinical assessment in the surgical outpatient clinic is to:

- evaluate the potential value of surgical intervention,

- provide further information to the patient of the risk/benefit ratio of a surgical procedure,

- confirm the feasibility of day surgery care for the individual patient.

When assessing the value of surgery, the primary decision between surgeon and patient concerns surgical intervention or the avoidance of surgery (i.e. the ‘do nothing approach’). This is a management choice which is often neglected and should be considered at the same time as discussing the risk/benefit ratio of the surgical procedure. It is important the patient is fully involved in the decision-making process and if possible, should receive written information about their future operation at this time. Possible complications and their frequency should be discussed, fulfilling the first part of patient consent. Decisions made by junior members of the surgical team should be verified by a senior surgeon before any procedure is confirmed and booked. At this point on the patient pathway, a decision regarding the feasibility of performing the surgical intervention on a day case basis should be addressed. The possibility of employing minimal-access techniques for the procedure may allow the conversion from overnight stay to day surgery.

The development of day surgery worldwide over the past 30 years has led to a rapid expansion in the number and variety of procedures performed. Any procedure is suitable for day surgery provided there is:

- Sufficient time for patient recovery before discharge (usually 4-6 hours after general anaesthesia).

- No ongoing requirements for intravenous fluids.

- No ongoing requirements for parenteral analgesia or antibiotics

- Minimal risk of postoperative haemorrhage.

- No specialist postoperative care or observation necessary

- Minimal tissue trauma either by the use of minimal access techniques or careful and gentle tissue-handling by the surgeon.

Reactionary haemorrhage may occur within 24 hours of surgery, but most commonly occurs within 4-6 hours, during the day surgery recovery period. Common causes include patient mobilisation, cessation of vasospasm, ligature slippage and clot displacement. If this occurs, the patient may easily return to the operating room. Secondary haemorrhage is commonly the result of infection eroding a vessel and occurs considerably later, usually after 7-10 days postoperatively and is therefore a risk after all surgery, whether day case or in-patient.

With modern multimodal anaesthesia, operating time is not as critical as it once was, although most procedures for day surgery require less than 2 hours anaesthesia time.

There is no definitive list of procedures suitable for day surgery. Each national association or government will have their own specific recommendations. However, if no guidelines exist, then the Directory of Procedures published by the British Association of Day Surgery may provide useful information. The Directory lists over 200 possible procedures which could be performed on a day case basis under optimal conditions (2).

Patient selection criteria are useful in predetermining the cohort of patients considered suitable for day surgery. With experience and the adoption of modern anaesthetic and surgical techniques, it is important selection criteria are reviewed and updated on a regular basis otherwise potential day case patients will be excluded from the pathway.

The most common selection criteria restrictions relate to easily identifiable clinical factors including:

- Age

- Body Mass Index (BMI)

- ASA Status (American Society of Anaesthesiologists)

Age: In the early years of day surgery, there was often an upper age limit for acceptance on the assumption that age was a proxy for comorbidities. With improved health in the elderly, biological rather than chronological age is now a better determinant of suitability for day surgery. The ability to manage Paediatric patients is determined by the experience of those providing the service. A minimum age should be agreed based on the skills available.

BMI: Obesity is defined by the World health Organisation as a BMI > 30kg m-2. The prevalence of obesity worldwide is increasing but many day surgery units still exclude patients with high BMI from day surgery. The ability to manage obese patients depends on the experience of the surgeons, anaesthetists and nursing staff involved as they can present a challenge over the perioperative period. With experience units now successfully manage selected patients with a BMI of up to 40 as day cases for a selection of procedures.

ASA Status: The American Society of Anaesthesiologists (ASA) classification system is used to assess the physical state of the patient prior to surgery and has been adopted worldwide and consists:

ASA Status | Patient pre-operative status |

1 | Normal healthy patient |

2 | Patient with mild systemic disease |

3 | Patient with severe systemic disease that is not incapacitating |

4 | Patient with incapacitating systemic disease that is constant threat to life |

5 | Moribund patient who is not expected to survive for 24hrs with or without an operation |

Patients ASA Grades I and II are readily accepted for day surgery. Grading of a patient as ASA 3 status should not automatically limit them to inpatient care, but rather, identify a need for optimisation by the anaesthetist to evaluate the possibility of day surgery. It has been demonstrated that with appropriate planning, no significant differences exist in unplanned admission rates, unplanned contact with health care services, or post-operative complications in the first 24 hours after discharge between ASA III and ASA I or II patients (3).

- Patients should be selected according to their physiological status not their age.

- Fitness for a procedure should relate to the patient’s health as found at pre-assessment and not limited by arbitrary limits such as ASA status.

- Obesity is not an absolute contraindication for day care in expert hands and with appropriate resources.

There are differing models of facility suitable for the provision of day surgery services. In the ‘stand-alone’ model, the day surgery unit is separate from the main hospital, either in the hospital campus or some distance away. This is a cost-effective way of performing day surgery, with dedicated facilities and fast throughput. The downside of this model is that failed day cases require an unplanned overnight admission bed, usually available at the parent hospital. Strict criteria for patient fitness are necessary to limit unplanned overnight admissions and this restricts the potential day surgery population. In the hospital-integrated unit, the day unit is part of the main hospital and may be required to accept unsuitable patients on a temporary basis when overall hospital facilities are stretched. This may result in cancellation of planned day surgery.

Regardless of structural model, the functional critical component is a dedicated day ward area rather than using an inpatient facility. Performing day surgery from an inpatient facility has been shown to carry a significant risk of unplanned overnight admission for the day surgery patient. The staff on the ward naturally focus on those patients they perceive to require the most assistance and it is possible the day surgery patient may be neglected and fail same-day discharge.

However, if appropriately managed, day surgery can be performed through many facilities but the dedicated unit remains the most efficient and cost-effective way of managing the day surgery workload. The dedicated day ward should have trolleys and chairs rather than beds. Hospital beds suggest to the patient the traditional inpatient pathway and a resultant reluctance to mobilise postoperatively, especially if bedside televisions are provided.

The operating room or rooms in the stand-alone unit are dedicated to the facility. In the hospital integrated unit, the operating room may be attached to the day ward or day surgery patients may use the main operating room complex.

Before the development of the day surgery pathway, patient assessment (and any tests such as ECG) was usually performed by a junior doctor the day before surgery at the time of the patient’s admission. This was followed by an assessment visit by the anaesthetist. Today, preoperative assessment is usually performed by dedicated team – in some countries e.g. UK this is a specialist nurse team with anaesthetic support whilst in other countries e.g. the Netherlands the Anaesthetists perform this task. The UK experience provides evidence that nursing staff can be trained to provide this service and are cost-effective and provide a consistent safe standard of assessment (4). The function of this service is to both assess the patient and provide the patient with additional information regarding their admission. This includes:

- Specific information about their procedure

- Arrangements for the day of surgery including fasting and management of medication pre-operatively

- Recovery from surgery including likely management of any postoperative pain.

Initial patient screening can be performed with the completion by the patient of a simple questionnaire to highlight areas where further enquiry might be needed, or additional information is required. This questionnaire can be provided by the primary care referrer, completed at the time of the outpatient visit or at the preassessment interview.

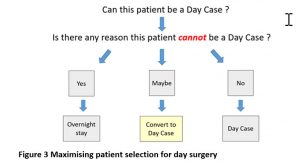

When assessing the patient for the possibility of day surgery, it is important to consider the ‘default to day surgery’ principle (figure)

One of the values of the preassessment team is in converting the maximum number of ‘maybe’ patients to day surgery. Where nursing delivery of the preassessment model is used this requires the assistance of the anaesthetist and dedicated anaesthetic sessions to provide the team with expert support to maximise the number of day surgery patients.

The timing of preassessment is also critical in determining the efficiency of the process. Local policy will determine the length of validity of preassessment (typically valid for 3 to 6 months). If performed too early, administrative delays may exceed the validity period and the preassessment may have to be repeated. Alternatively, the patient in the meantime may relocate to another part of the country or may even change their mind regarding the operation itself. In contrast, when preassessment is performed in close proximity to the day of surgery, the scheduled patient may not be available, or the assessment may identify unforeseen comorbidities leading to a late cancellation and operating room slot unfilled.

Performing preassessment at the time of the surgical outpatient consultation is the best model of care as it avoids the need for reattendance by the patient. If this is not possible, either due to patient or preassessment team availability, then interval preassessment is appropriate and may be conducted ‘face-to-face’, by telephone or even on-line. The decision to offer telephone preassessment is based on the perceived fitness of the patient for the procedure to be performed. Telephone preassessment is ideal for the younger, fitter patient especially if uncomplicated surgery is planned or the procedure is scheduled to be performed under local or regional anaesthesia.

All patients require their blood pressure to be measured. It is not uncommon to find isolated raised blood pressure at preoperative assessment due to the stress and anxiety of the consultation. If blood pressures are below 180mm Hg systolic or 110mmHg diastolic, there is little value in deferring surgery, though additional investigations such as an ECG or U&Es may be performed to indicate presence of associated cardiac or renal end organ damage. There is little evidence of an association with adverse cardiovascular events in the peri-operative period with this cohort of patients having day surgery (5). Patients with blood pressures higher than these levels are more prone to perioperative ischaemia, arrhythmias and cardiovascular lability and warrant review by an anaesthetist to decide on an appropriate peri-operative management strategy.

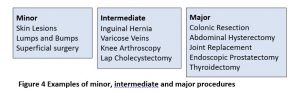

Routine investigations (ECG, blood tests) on the healthy patient are unnecessary and costly. A structured history and targeted examination by experienced staff is sufficient. Safe and cost-effective preassessment is based on algorithms considering the fitness of the patient and the complexity operation to be performed: minor, intermediate and major. (Figure 4)

Patients undergoing day surgery should be admitted on the day of surgery to the dedicated day unit, not a mixed inpatient ward. Performing day surgery from an inpatient facility carries a significant risk of unplanned overnight admission for the day surgery patient. The staff on the ward naturally focus on those patients they perceive to require most assistance and the day surgery patient may be neglected and fail same-day discharge.

The same principle of day of surgery admission can also be applied to patients requiring an overnight stay in hospital after their surgery. Many hospitals have created, in addition to their dedicated day unit, ‘admission lounges’ or Day of Surgery Admission (DOSA) units where patients scheduled for overnight stay can be admitted before going to the operating room. After surgery, the patient returns to the in-patient ward, thereby saving an overnight stay before surgery.

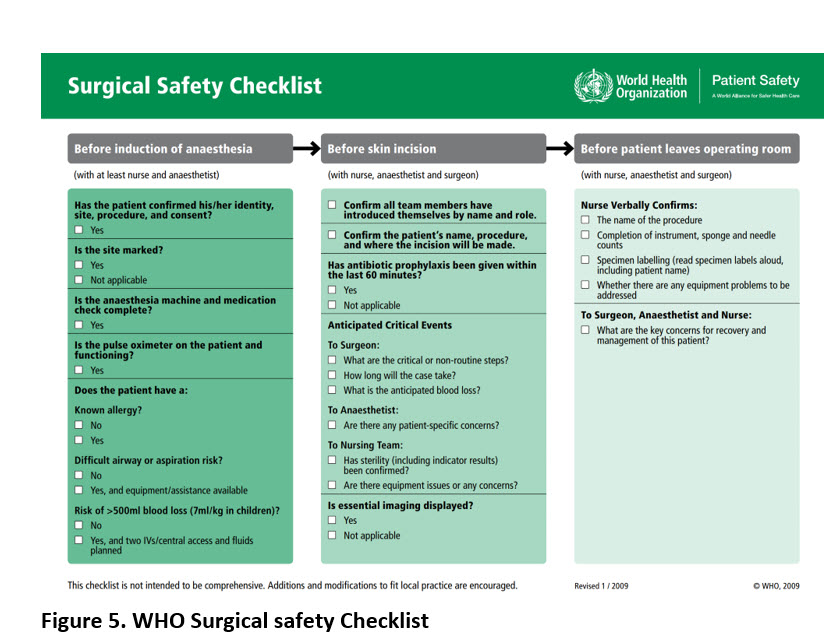

The World Health Organisation operating room briefing, and safety checklist (6) has not only improved patient safety but also improved efficiency through better communication among all the healthcare professionals involved. It is recommended that day surgery units follow this checklist or an equivalent nationally agreed checklist that may have additional components. (7)

The Preoperative Checks performed before surgery include patient consent, marking of the side and site of surgery and a venous thrombo-embolism (VTE) assessment. VTE assessment is certainly required for inpatient surgery, and if at risk, mechanical (stockings) or pharmacological (heparin) prophylaxis is required. Remember any patient who is a failed day case requiring an unplanned overnight admission requires VTE reassessment after surgery to minimise VTE risk. As day surgery expands, more major operative procedures are now being performed, and although these patients are ambulant soon after surgery, VTE prophylaxis is still prudent, despite the lower risk of deep venous thrombosis and pulmonary embolism.

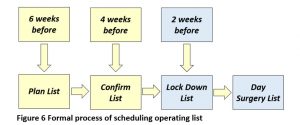

The scheduling of surgical procedures requires advanced planning for the admissions team in booking the patient and the scheduling team to formulate the content and order of individual lists.

Advance planning

As day surgery consists of mainly elective procedures following a defined and scheduled pathway, the last-minute cancellation should be a rare event. Operating lists should be planned many weeks ahead with potential patients contacted. If not already conducted, preassessment should be performed before the list is confirmed at least 2 weeks before. The process shown in Figure 6 demonstrates the countdown schedule.

Operating list format

Individual day surgery operating lists generically may be formed in three ways:

1. Dedicated day surgery lists

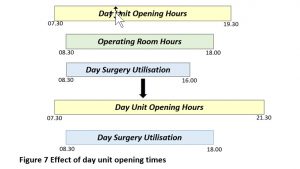

The formal separation of day surgery patients onto dedicated specific operating lists within an autonomous Day Surgery Unit with its own ward remains the most efficient model of care. Major cases should be prioritised to morning sessions or at least, the early part of afternoon sessions. Day surgery patients require time to recover before same-day discharge. Consideration should be given to opening hours of the unit and the ward discharge area in particular. Early evening closure of the day ward limits day surgery in the operating room. (Figure 7) However, by extending the day ward opening hours to later in the evening, the afternoon operating session can be fully utilised for day cases.

2. Dedicated day and short stay lists

This model of care offers the possibility of performing day surgery mainly on morning lists and patients requiring an overnight stay may then be scheduled for afternoon lists. While in theory this model should maximise day surgery in the hospital, individual surgeon allocation often results in mixed lists of day surgery and overnight stay patients in the morning and in the afternoon sessions.

3. Mixed lists of day and major inpatient surgery.

While this pattern of scheduling would appear to offer maximum flexibility for day and inpatient cases, in practice it is often an inefficient and poor-quality pathway. Starting the list with a day case before more major surgery often delays the start of the major case for which the anaesthetist may require time for the insertion of invasive lines or epidural. Most surgeons prefer an early start for major surgery so that in the event of a significant complication, resolution of the problem occurs late afternoon or early evening when full clinical resources are readily available rather than requiring an out of hours solution. However, scheduling a day case after major surgery may also cause a problem as complex surgery may over-run resulting in cancellation or unplanned overnight admission for the day case, especially if the surgery is left to a more junior member of the operating team.

Individual Patient Requirements

When constructing a day surgery list, it is important to consider the needs of the individual patient. The very young do not tolerate fasting for long and therefore require early scheduling. Similarly, the elderly need an early slot but for the different reason of allowing maximum time for recovery before discharge as they are often confused following general anaesthesia. Specific comorbidities may require early scheduling. Patients with diabetes should be prioritised first on the list. Their morning medication, whether oral or injection is withheld, their procedure is performed and as soon as they are eating and drinking immediately postoperatively, their medication is then administered. For most day surgery patients, insulin infusions are unnecessary.

Patients who are required to adopt a prone position for their surgical procedure may require an endotracheal tube to secure the airway rather than laryngeal mask anaesthesia and may therefore require a longer recovery time, so are best treated early on the operating list.

Maximising Efficiency

The indicative operating time for a specific procedure is dependent on the anaesthetic preparation, the surgeon’s operating time and the turnaround time between cases. Accurate data on the time taken to perform a specific procedure allows maximum usage of operating room time. This time will vary according to whether the operation is performed by a consultant or a trainee, especially if teaching is involved. It is possible, with sufficient data, to estimate indicative operating times for specific procedures performed by individual consultants and this offers the most accurate estimation of operating time to maximise operating room throughput.

When running a day surgery operating list with multiple cases during the day, it is important to keep the turnaround time as short as possible and this paradoxically requires more operating room nurses to maintain efficiency when compared to operating lists consisting of one or two complex major cases.

Protocol-based discharge

Medical staff with their multiple commitments are often unable to review and discharge their patients when the patient is fit to leave. The solution for day case patients is to allow discharge in the absence of medical staff based on strict discharge protocols. Once the patient has fulfilled the criteria listed on the protocol, they may be discharged by the day unit nursing staff. An example of a protocol-based discharge is shown in figure 8. The advantage of this system over scoring systems is that it includes important criteria e.g. has responsible person to take them home.

- Vital signs stable for at least 1 hour

- Correct orientation as to time, place and person

- Adequate pain control and has supply of oral analgesia

- Understands how to use oral analgesia supplied and has been given written information about these

- Ability to dress and walk where appropriate

- Minimal nausea, vomiting or dizziness

- Has at least taken oral fluids

- Minimal bleeding or wound drainage

- Has passed urine (only after certain procedures not required for most)

- Has a responsible adult to take them home

- Has an agreed carer at home for next 24 hours

- Written and verbal instructions provided about postoperative care

- Knows when to come back for follow up (if appropriate)

- Emergency contact number supplied

Figure 8 Discharge protocol

Modern discharge criteria no longer require the oral intake of fluids as a prerequisite before discharge as patients who are strongly encouraged to drink prior to discharge are more likely to suffer from post-operative nausea and vomiting (PONV). Similarly voiding before discharge in patients with a low risk of urinary retention is no longer considered necessary. Patients at higher risk if unable to void, should have a bladder ultrasound performed to assess bladder volume and determine the need for catheterisation. High risk patients include men > 50 years old, spinal anaesthesia, inguinal hernia repair, anorectal procedures such as haemorrhoid or fistula surgery and prostatic procedures.

Minimum periods of patient observation are only necessary for a few specific procedures (e.g. tonsillectomy) with potentially serious complications that may occur shortly after surgery. Once a patient achieves the milestones of haemodynamic and “vital sign” stability and normality, adequacy of analgesia, dry incision site and mobilisation, there should be no artificial time-based embargo placed upon discharge.

The Journey Home

After a patient has received sedation or general anaesthesia, they will have significant postoperative psychomotor and cognitive impairment and therefore should not drive themselves home. This impairment may last up to 8 hours postoperatively, depending on the anaesthetic agent. However, patients may have experienced anxiety, sleep deprivation or postoperative pain and may also be under the influence of analgesia and antiemetic drugs which may reinforce any impairment. As a result, the sensible advice is for the patient to avoid driving for at least 24 hours after their procedure. A further factor which may influence the time to return to driving, is the nature of the patient’s surgery and further limitations may be imposed after procedures such as hernia repair, ophthalmic surgery or orthopaedic surgery. The practical advice to the patient is therefore to ask them to ensure they can complete an emergency stop in a controlled situation before recommencing driving.

For the journey home, it is advisable the patient is accompanied by an escort to ensure patient safety on the journey. To be eligible for day surgery, most hospitals would recommend:

- The patient’s escort should be a ‘responsible adult’.

- The patient should live no more than a one-hour journey from the hospital.

- The journey should not involve public transport.

These apparently sensible precautions may nowadays be too restrictive and open to interpretation. The definition of a responsible adult is ill-defined and the term ‘responsible’ in this context refers to being accountable and competent. Clearly an escort under the influence of alcohol or drugs might be refused custody of the patient by the discharge nurse. Similarly, the term ‘adult’ varies in different countries and the practical solution is to consider the designated escort according to their maturity and responsibility, even if only a teenager.

The advice to patients regarding travelling time after day surgery is outdated and with modern analgesia and antiemesis, many patients are comfortable to travel for longer than one hour. The advice to avoid public transport is valid. There is a risk of inadvertent jostling causing operation site discomfort, or discomfort when embarking or disembarking a bus or train. Public transport may not always be reliable. However public taxis are clearly suitable and an exception to this rule.

Help at home

The concept of an elderly patient requiring help at home is well-founded. Their return home is often a worry and any physical disability as a result of their operation is often magnified and is a source of concern as to how they will cope with everyday activities in the immediate postoperative period. Add in the lingering effects of sedation and anaesthesia, and it is quite clear that it is essential to have help present on the first night home as the patient adjusts to their new situation.

For others, the situation is less clear. Many people nowadays live alone, and unless essential, many would prefer not to have anyone accompanying them at home in the postoperative period. Nevertheless, patient safety is a priority.

A pragmatic approach is to ensure anyone who could suffer covert bleeding, as with operations in the abdominal cavity, such as laparoscopic cholecystectomy, should have help available on the premises and able to act if the patient’s health deteriorates. For others where the surgical procedure is non-invasive, such as hernia repair or removal of ‘lumps and bumps’, any postoperative haemorrhage is overt and take the form of a haematoma or be controllable with simple pressure. Where the patient is aware of their complications, the availability of nearby help, contactable by telephone, is all that is required. Procedures where postoperative bleeding can affect the airway, such as after tonsillectomy or thyroid surgery, then the presence of help at home actively monitoring their charge is essential.

Post-Discharge Support

A 24-hour telephone number must be supplied so that every patient knows whom to contact in case of postoperative complications. Thereafter, the models of post-operative care are:

Routine follow-up phone call to the patient next morning by a member of the day unit team who as well as ensuring the patient is well, asks a series of set questions and records the results.

The alternative is to provide a dedicated number that the patient can ring should they wish advice or further information.

Both systems have their merits. The routine call often prompts questions to allay patient’s anxiety where the patient would not have bothered in the on-demand model. The onus on the patient to call in if they have problems or questions suits those who value their independence.

- Nicoll JH. The Surgery of Infancy. British Medical Journal. 1909. Vol. ii pp 753-756

- BADS Directory of Procedures. Sixth Edition. 2019. British Association of Day Surgery. London.

- Ansell GL, Montgomery JE. Outcome of ASA III patients undergoing day case surgery. British Journal of Anaesthesia 2004; 92:71–4.

- Kinley H, Czoski–Murray C, George S, et al. Effectiveness of appropriately trained nurses in preoperative assessment: randomised controlled equivalence/non–inferiority trial. British Medical Journal 2002;325:1323-8.

- Howell SJ, Sear JW, Foex P. Hypertension, hypertensive heart disease and perioperative cardiac risk. British Journal of Anaesthesia 2004;92:570-83.

- Haynes AB, Weiser TG, Berry WR et al. A Surgical Safety Checklist to Reduce Morbidity and Mortality in a Global Population. N Engl J Med 2009; 360:491-499

- de Vries EN, Prins HA, Crolla RM et al. Effect of a comprehensive surgical safety system on patient outcomes. N Engl J Med 2010;363:1928–37.